Systemic persecution, mass arrests, and manufactured starvation have become the lived reality of the Bawm community of Bangladesh, an ethnic group of just over 12,000 people residing in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). Over the last two years, abuse and violence carried out by the military in the name of “national security” have intensified, creating a deadly situation for the Bawm. Fear of persecution and military crackdowns has displaced around 3,500–4,000 Bawm individuals—roughly one-fourth of the community. According to a statement signed by CHT Commission co-chairs Sultana Kamal, Elsa Stamatopoulou, and Myrna Cunningham Kain, many have been forced to seek refuge in Mizoram (India) and Chin State (Myanmar), living in precarious conditions. The indiscriminate harassment of the Bawm people by state security forces is carried out under the pretext of suppressing the Kuki-Chin National Front (KNF), a fringe armed group that has been used as a convenient justification for military occupation and for silencing any calls to demilitarize the CHT.

This escalation of violence must be understood within a broader history of repression, military reprisals, land grabbing, and dispossession faced by Indigenous communities in Bangladesh since independence. The post-1971 state constructed its national identity around the standardized identity of “Bengali,” sidelining Indigenous communities who possess distinct languages, cultures, and identities. The 1997 Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord, signed between the government and the Parbatya Chattagram Jana Samhati Samiti (PCJSS), promised to end conflict and address systemic injustices. Nearly three decades later, however, the Accord remains largely unfulfilled. Instead of withdrawing military encampments, the occupation has deepened. Instead of recognizing Indigenous land rights and granting Hill District Councils administrative control, the central government has tightened its chokehold. Development projects, settlement initiatives, and expanded military camps have dispossessed Indigenous peoples of their land and homes. State-backed violence has been reinforced through contested laws such as the Special Powers Act and the Anti-Terrorism Act—frameworks that contextualize the harrowing abuses now faced by the Bawm community.

In April 2024, following a KNF-linked bank robbery in Ruma and Thanchi of Bandarban, the army launched a massive campaign of arbitrary arrests against the Bawm in the name of a “joint operation.” While enforced disappearances and arrests had already been taking place in 2022 and 2023, the robbery provided new justification for unchecked repression. One family member of an arrestee reported that the military gathered villagers on school grounds, separated men and women, and selected people at random for arrest—including women with children, students, and the elderly. Taken to Bandarban police station, they have remained detained under multiple fabricated cases and denied legal representation.

Custodial Deaths

This systemic injustice has claimed at least three Bawm lives in custody.

- Lal Thleng Kim Bawm (29) was arrested under false charges and held in Chittagong Central Jail for over a year without trial. Despite deteriorating health, he was denied medical treatment. On April 15, 2025, his condition worsened; he was rushed to Chittagong Medical College Hospital (CMCH) but was dead on arrival.

- Van Lal Rual Bawm (35) went missing in February 2023. His family later discovered he had been picked up by joint forces and falsely charged. After more than two years in pre-trial detention, he fell critically ill in July 2025 and died shortly after being transferred from prison to CMCH.

- Sang Moy Bawm (55), imprisoned for two years on fabricated charges, suffered from underlying conditions compounded by medical neglect. He was abruptly granted bail on June 29, 2025—an attempt to avoid liability for custodial death. He died at home two days later.

Imprisoned Women and Denial of Medical Care

The fate of Shiuli Bawm (21), arrested in April 2024, remains dire. She suffers from thalassemia and has been denied regular blood transfusions in Chittagong Central Jail. Despite urgent health concerns, her bail applications have been repeatedly rejected by both lower courts and the High Court. Similarly, Lalnun Kim Bawm (25), a stroke patient arrested with her sisters, has been denied consistent medical treatment despite doctors’ recommendations.

Other detainees, including Lalthanhakim, Partha Jual, Tina, and Mallory, have had bail granted by the High Court only for their release to be blocked by subsequent stay orders from higher courts. After 503 days of detention, Leri Bawm and four other women were finally granted bail in August 2025—yet their release remains precarious, given the state’s record of appealing bail rulings.

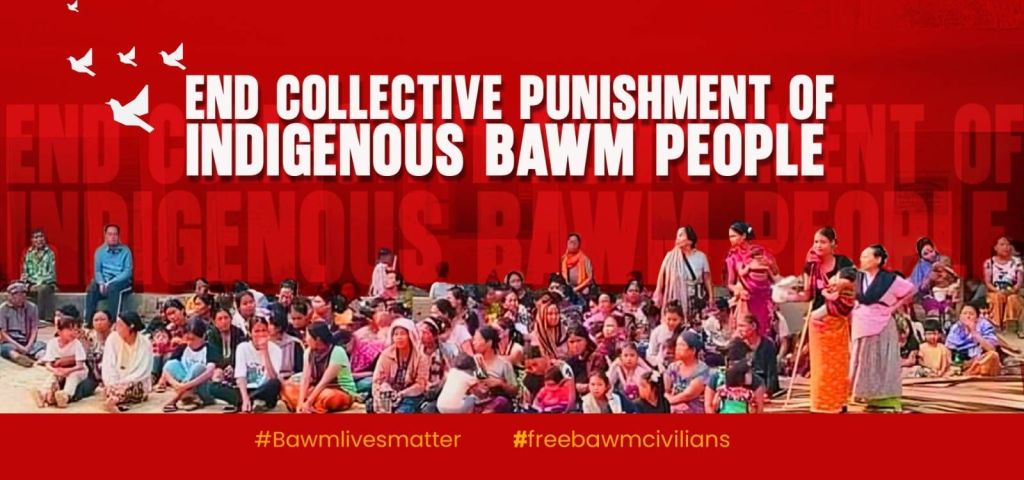

Collective Punishment

Those not imprisoned endure daily harassment and collective punishment. Military checkpoints and random searches restrict mobility. Rice purchases are limited to 1 kg per family, only with military-issued slips, effectively weaponizing starvation. Night raids terrorize villages. On May 23, 2024, 13-year-old Van Thang Pui Bawm was shot dead in his home in Bethany Para, Bandarban, when the military indiscriminately opened fire during an operation. Instead of accountability, media outlets sought to label him a KNF member. A Netra News investigation revealed that since April 7, 2024, at least 22 Bawm civilians have been killed and 200 arrested under false charges.

Resistance and Demands

The custodial deaths sparked the “Bawm Lives Matter” campaign. On August 2, 2025, 150 civil society members issued a statement demanding:

- An independent judicial inquiry into custodial deaths and arbitrary arrests.

- The immediate release of all wrongfully detained Bawm individuals.

- An end to collective punishment, harassment, and restrictions on Indigenous peoples’ mobility.

- Freedom from state interference in essential purchases and economic activities.

Until these demands are met, the Bawm community remains trapped under state-sanctioned violence, denied justice, and subjected to slow erasure.