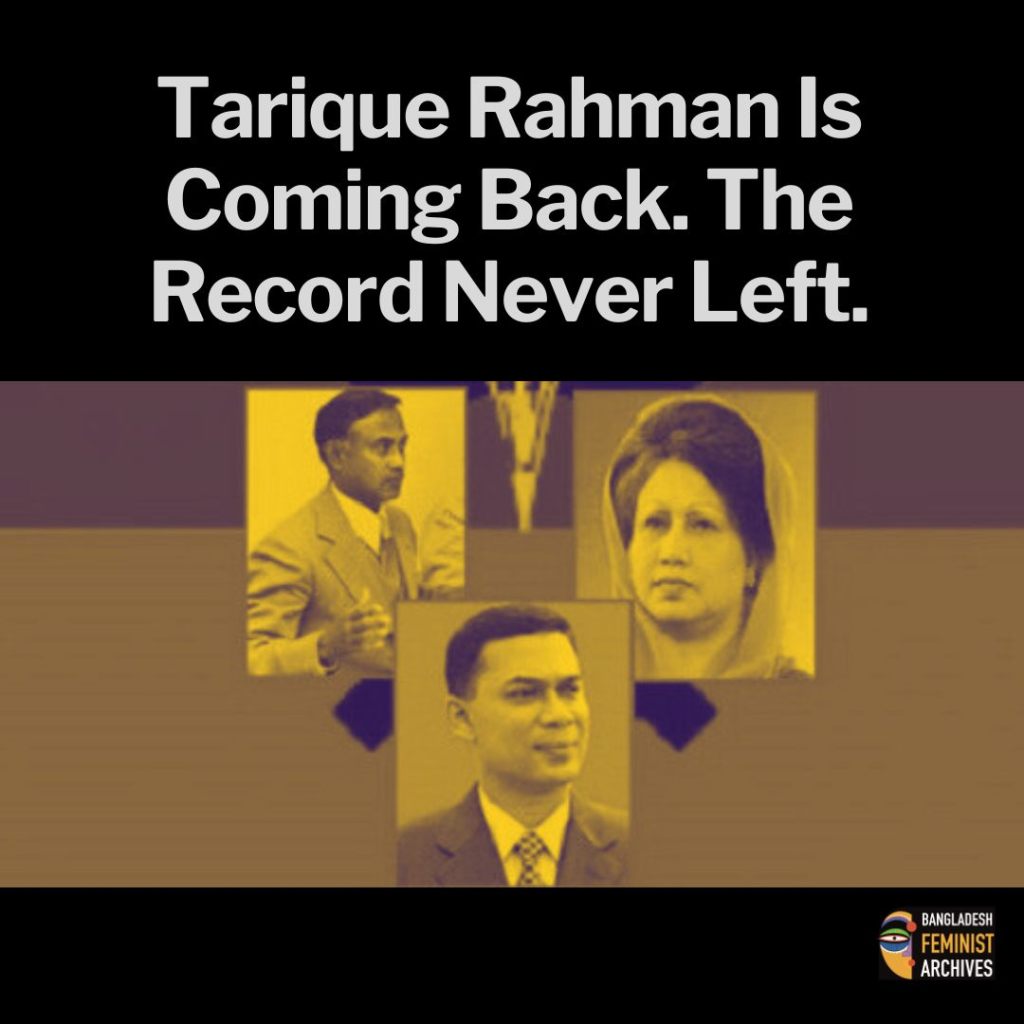

Tarique Rahman entered Bangladeshi politics through lineage rather than electoral mandate. As the elder son of former president Ziaur Rahman and former prime minister Khaleda Zia, his political ascent was shaped by dynastic access. Despite holding no constitutional office, he emerged as a central power broker during the 2001–2006 period.

That power operated informally through Hawa Bhaban, widely documented as a parallel authority influencing state contracts, security decisions, and political appointments. This period is legally and historically recorded as one marked by systemic corruption, intimidation of journalists, suppression of dissent, and the erosion of institutional accountability. Multiple corruption convictions later confirmed these practices as matters of record, not allegation.

The same period saw widespread post-election violence, particularly against religious minorities. Human rights documentation details rape, arson, displacement, and intimidation, especially targeting women, as forms of political punishment. Sexual violence functioned within a climate of impunity sustained by political power, not as isolated criminal acts.

In 2004, a coordinated grenade attack on a political rally killed and injured scores. Courts later convicted Tarique Rahman in absentia for involvement and sentenced him to life imprisonment. He left Bangladesh in 2008 and remained abroad for years, avoiding extradition while retaining political influence from exile.

On December 25, 2025, Tarique Rahman is expected to return to Bangladesh. In recent years, he has adopted a markedly different public persona, speaking the language of democracy, restraint, and institutional reform, rhetoric sharply at odds with the documented record of his political career.

The question Bangladesh faces is not whether political figures can change tone, but whether a future can be built without reckoning with corruption, gendered violence, and authoritarian practice. Without acknowledgment or accountability, return risks becoming repetition.